Baseball Stories

A crack-of-the-bat flashback

Whack!!

At the crack of the bat, my head pops up, and I fly line drive…to the ’50s of my formation.

The 1950s were, at least on the surface, a special, innocent, almost idyllic, time in American middle class life. Dwight Eisenhower was president, we lived on a cul-de-sac in suburban Los Angeles, there was a swimming pool in the backyard, and the family’s Dodge sedan and Ford station wagon were parked in the driveway because the garage was home to all manner of household stuff: bicycles, roller skates, scooters, garden tools, baseball bats and mitts, suitcases, and a chest freezer. Our house faced the street with used brick and light green lap siding; sides and back were stucco, the roof shake-shingled.

Dad had a professional career as a deposition reporter and worked from home much of the time. Mom also worked at home: the quintessential homemaker, she cooked, cleaned, shopped, did laundry, and hustled us kids off to school. To top it off, almost every evening all of us of could be found having dinner at the round, metal table tucked into the dinette end of the kitchen.

Pretty much an Ozzie and Harriet kind of life. It was a life we shared with the Nelsons via the bulky block of blond furniture in our rumpus room called a Packard Bell TV. Seamier sides of the ‘50s – Jim Crow, the Korean War, McCarthyism, and downtown L.A.’s skid row, for example – were barely in range of the antenna adorning the house over our heads.

Dad, contrary to his desk job, was quite athletic. He played baseball shortstop and basketball forward in high school and college and earned many a trophy in B’nai B’rith bowling leagues. When he wasn’t otherwise occupied pulling weeds or tending his beloved rose garden or backyard barbecue, Dad would often invite brother Gary and me to play catch with him in the street after school. Though also invited, sister Jean declined lest a wayward baseball hit her bespectacled face.

When we first moved to Studio City from Burbank, there was no local Little League team in those early days of the suburbanizing San Fernando Valley. So, Dad took the initiative, organized other dads together, and created one. I felt so proud all suited up, clickety-clacking cleated shoes across the kitchen linoleum, and trying my hand and glove at first base or on the pitcher’s mound. Dad, as team coach, quickly recognized my blossoming baseball abilities and aptly assigned me mostly to the bench position.

When I aged out of Little League, Dad once again went into community organizing action. Now, Pony League Coach Dad once in a while asked me to fetch fly balls in right field. Again, my playing prowess, though, appropriately consigned me to the sidelines as the team’s official scorekeeper. Truth be told, though uniformed, cleated, and ready to play, it was actually a relief to be on the bench instead of in the field. I felt such satisfaction and sense of fulfillment recording on the score sheet the story of each pitch of the ball, each swing of the bat, and each run crossing the plate. Whether Coach Dad was aware of it or not, it turns out that role tapped into an innate talent of mine that foretold my later career in math and statistics. Thanks, Dad!

That ability-appropriate bench playing also launched in me a lifelong love of baseball as a fan in the stands. This love was fanned whenever Dad would drive Gary and me over the hill to L.A.’s Fairfax district to watch the Hollywood Stars at Gilmore Field.

In those distant days, the almost-major minor league Pacific Coast League was the only source of pro baseball this far out in the Wild West hinterlands (as East Coasters likely thought of us). There were two PCL teams in Los Angeles, the inevitable archrival Hollywood Stars and Los Angeles Angels. To this day, I relive with relish the amalgamated aromas of hot dogs with mustard, smoke swirled from cigars, bulging bags of buttered popcorn, pink clouds of cotton candy, and the leathered gloves we’d wear in hopes of snagging a passing pop foul as it flew over the screen on the first base side of home plate. I felt a special thrill one day as I scrambled over rows of seats to just below the broadcast booth, from where I watched Mark Scott, whom I normally listened to adoringly from home, calling the play-by-play for the poor souls glued to their radios. And, oh, the scrumptious sounds of the game! Especially satisfying was the smack of a successfully swung bat, of ash crashing into horsehide, sending the cheering crowd as one to its feet as the ball soared out of sight over the left field fence and into who knew what adventures awaited it beyond.

But, alas, each of those flashback moments was no static still but merely one frame of a motion picture that, inevitably, had to roll its reel. The very much major league Dodgers came to town, the Hollywood Stars faded into Wikipedian history, Mark Scott made way for Vin Scully, and Gilmore Field was razed to make way for CBS Television City and its parking lot for the cars of other stars. And I made my way through high school, college, and life.

And then, decades later and hundreds of miles away, while out for a walk…

Whack!!

At the crack of the bat, my head pops up, and I know what it is.

Sure enough, the ball comes sailing over the schoolyard fence to my right, bounces along the street, comes to rest at my feet. Of course I pick it up. How could I not? It’s that Gilmore homer come home at last.

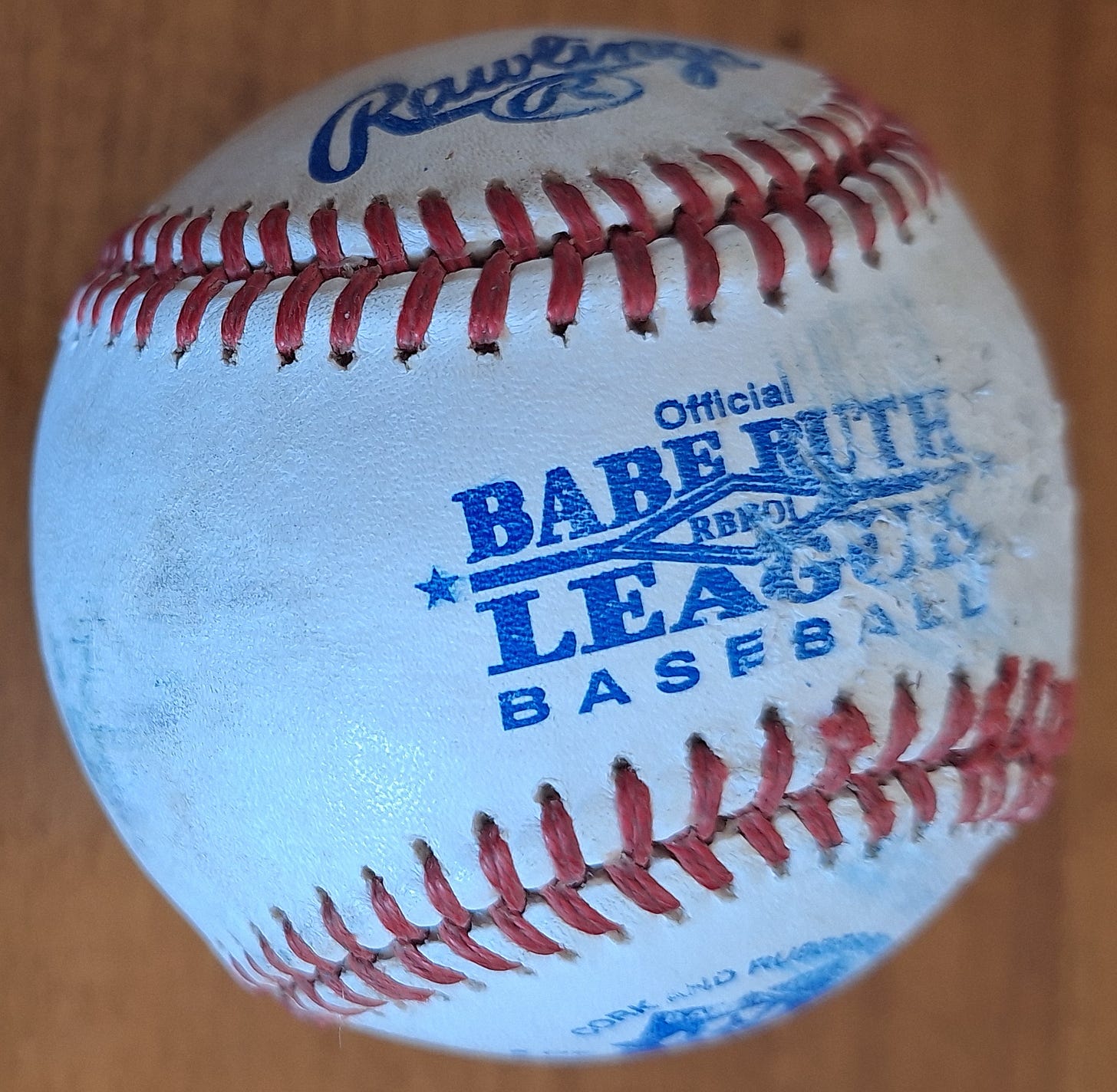

The ball, smudged, scraped, and scarred as it is, now sits on my desk. Often, I pick it up, stroke its rough, sinuous seams, grasp it firmly in my fingers as if to pitch to a batter or throw a runner out. Each smudge, scrape, and scar, I imagine, each yard of yarn wound tightly round the rubber cork core tells a story in the life of the ball, a story waiting to roll from the movie reel.

As your cousin and a fellow baseball lover, I truly enjoyed this piece, filled with childhood memories , and devotion to the game of baseball!🩷 Ginny